One of the Great Recession’s Biggest Culprits Is Back

Macro Update: This Tool Could Predict the Next Crisis – If It Doesn’t Trigger It First

The more things change, the more they stay the same.

The financial world is still trying to catch its breath following the last few weeks. After Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) rapid collapse shook people’s faith in the stability of other banks, a crisis swept through the industry as depositors started withdrawing their money.

That led to small players like Signature Bank and Silvergate as well as larger ones like Credit Suisse going belly-up and relying on bailouts from the government or other banks.

Since then, the government has stepped in and injected more liquidity to try to stop this contagion from tanking the economy. But plenty of investors are still worried these events are just the warm-up for another 2008-style catastrophe that’s just around the corner.

In fact, they might have a good reason for their suspicions. If you look closer, there’s a familiar culprit lurking behind the recent banking turmoil.

It was the most popular insurance tool of the financial market 15 years ago, when it made headlines for being one of the key drivers of the Great Financial Crisis.

That infamous insurance tool is a credit default swap, otherwise known as a CDS.

Just what exactly is a CDS, and how did it almost trigger another financial crisis?

Today, let’s walk through the mechanics of the CDS and how it functions in the world of financial markets.

Ben Lilly here. As you know, we want to take Espresso to the next level. To do so, we’ve explored bringing sponsors into our newsletter, but in a way that first and foremost benefits you, our readers. To that end, we aim to share introductory offers that give you an opportunity to trial new services, tools, or exchanges.

We are excited to announce our first sponsor, the trading platform ByBit. For those who have been looking for a new exchange, consider checking them out.

They operate in 160 countries. They have more than 270 assets trading on spot and over 200 perpetual and quarterly futures contracts. They even offer options contracts and NFT trading.

Simply put, ByBit has a lot to offer any trader. And right now, they are offering a $10 welcome bonus if you open a new account and complete some introductory tasks. They also have additional ways for you to earn.

So if you are looking for a new platform to trade on, consider ByBit today by clicking here. Also, if you simply want to support Espresso and the Jarvis Labs team, consider giving a click.

A Different Type of Insurance

At its core, a CDS isn’t that different from other forms of insurance for your car or your healthcare.

In a very simple manner, a CDS protects the capital of an investor who owns a bond, should the bond issuer default.

For example, say you invested $1 million in a bond issued by United Airlines (UAL). But as time goes on, with the amount of geopolitical turmoil and the potential for an energy crisis, you start to feel that United might have cash flow issues coming up. That would give it a high probability of declaring insolvency before the bond matures.

So you decide to take out an insurance policy to protect your $1 million investment. You call up an investment bank, such as Goldman Sachs, and ask them to write you an insurance policy – also known as a CDS – to protect the $1 million you invested in the UAL bond.

Goldman agrees to sell you a CDS, and you pay them a premium for taking on the default risk of the UAL bond.

Should the issuer (United Airlines) of the bond be unable to meet the debt liability and default on repaying the bond, Goldman will pay you the $1 million you invested in the now-defaulted bond.

If UAL does not default on the bond and pays you at maturity, Goldman will just keep the premium you paid them.

This is called a single-name CDS, and it’s the most common type of CDS. But there are other varieties.

Functionally speaking, a CDS is designed to cover more than just credit default risks. Trigger events such as bankruptcies and credit rating downgrades are risks that can be protected with a CDS.

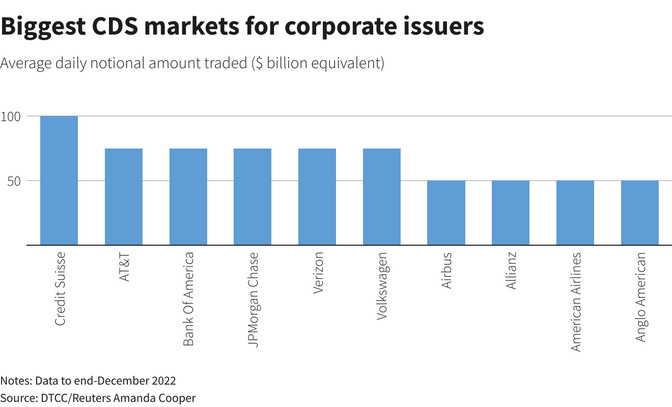

Below is a chart of the largest CDS markets by corporation. In other words, it shows the companies that have the largest amount of CDS taken out against them in 2022.

It is not surprising that financial institutions and telecommunication providers make up the top half of the list.

As we mentioned in our update a couple of weeks ago, financial and telecom companies’ bonds make up a large chunk of the BBB tranche, which has the largest amount of bond issuance across the corporate bond market. Plus, these bonds are usually considered relatively safe, but rising rates have started to chip away at their stability.

All of the above has led to more speculation these bonds might default, which drives up demand for CDS.

So how does a seemingly innocuous tool to hedge credit-default risk manage to turn rogue and spell trouble for markets?

In the Spotlight Once Again

The 2008 Great Financial Crisis propelled CDS to the center stage. But more specifically, it was a tool called a naked CDS that played a main role in the mess.

A naked CDS does not require the buyer of the CDS to own the underlying asset that he or she intends to insure against. It’s simply a tool for speculation.

Going back to the example of the UAL CDS, let’s say another investor has the same view on United as you do that it will not be able to fulfill its debt obligations. So that investor also decides to buy a $1 million CDS on the same bond you own.

The difference here is that while you bought the CDS because you own the bond and want to protect your investment, the other investor does not own the bond and is merely speculating to make some fast cash.

This strategy means that naked CDS buying can lead to some absurd market distortions. Imagine that the UAL bond’s actual balance is $350 million. Because any investor can buy a naked CDS on that bond, the notional balance (the balance of derivatives instruments using this bond) can be 5, 10, or 15 times the actual balance of the bond issued.

This is how the CDS market back in 2008 ballooned to a behemoth $57 trillion.

Many CDS were tied to mortgage-backed securities (MBS), and once those started defaulting, that triggered huge payouts to the CDS owners the likes of which were never seen before. It almost tanked the entire global economy because the CDS sellers could not come up with the liquidity to cover the payouts they had to make.

Today, the CDS market is $3.8 trillion, a fraction of what it was before.

But naked CDS still present a moral hazard. That’s why they’re more regulated today than they were 15 years ago. Some countries and regions, such as the European Union, have even banned them.

Since the buyer of a naked CDS does not own any of the underlying assets, the only way for them to get paid is for a default to be triggered.

This means it is in the naked CDS buyers’ best interest to scheme and manipulate the market to cause a default.

With the help of social media platforms nowadays, that is not hard to do.

Just ask Silicon Valley Bank.

While SVB’s demise was partly self-inflicted, social media also played a big role. The hysteria created by Twitter and Facebook over SVB’s financial situation accelerated its downfall and pushed it past the point of no return.

Another problem with a naked CDS is that it can actually be a self-fulfilling prophecy.

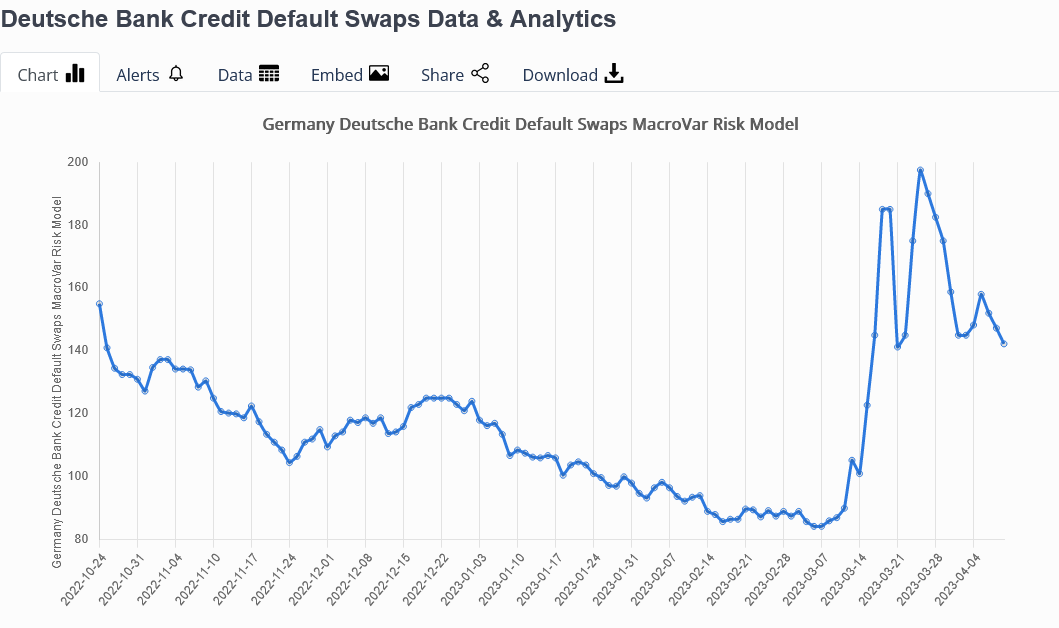

The chart below shows CDS premiums over the past six months for Deutsche Bank (DB), another institution that got caught up in the post-SVB banking turmoil.

Notice the sharp spike on the right side of the chart. It started on March 9 – right around the same time as Credit Suisse was going insolvent.

A lot of people were speculating that since DB has a profile somewhat similar to Credit Suisse, it might not be able to pay back its debt holders either. So investors piled in and bought CDS for DB’s debt liabilities, hence the big spike in the CDS premium. The demand outstripped the supply.

However, this had the knock-on effect of other people, specifically DB’s depositors, seeing the sharp rise in the premiums and thinking they were a sign that DB will be insolvent soon. After all, CDS is an insurance policy. If the sellers are charging hefty premiums, that must mean that DB will be going under.

This resulted in more and more depositors wanting to withdraw money from DB and thus creating a bank run. Then, the CDS premium shot up even higher, and thus even more people wanted to get their money out of the bank.

This is a negative feedback loop.

It’s how buying a naked CDS can turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If the repercussions are severe enough, the issuer of the bond – whether it is a bank, company, or country – will be put in a compromised position and default on its debt obligations.

Which is exactly what the naked CDS buyers are going after.

Thank you for reading Espresso. This post is public so feel free to share it.

Harbinger of the Next Crisis?

A CDS is a classic example of good intentions gone wrong.

What was supposed to be a method of risk management, hedging, and investment protection has morphed into an effective gambling tool to not only earn profits off of the unfortunate demise of either institutions or sovereignties, but also to cause them.

But because of this, that means they can be used as a canary in the coal mine to see what is coming down the pipe.

For instance, another potential piece in this global economy Jenga puzzle is the health of the global commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) market.

We’ve all heard stories of office space vacancies skyrocketing, thanks to the new work-from-home model and COVID-19 forcing shopping malls and brick-and-mortar retail centers to shut down. As a result, CMBS are in a rough spot at the moment.

Lack of tenants means lack of revenues for commercial real estate owners, which makes it more difficult for them to keep up with the mortgage. Headlines talking about increases in commercial mortgage delinquencies are popping up more often.

Should delinquencies keep rising, CMBS will most likely start to default on bond repayments, because their underlying assets are the commercial mortgages that provide the monthly cash flow.

And as default risk increases, the premiums charged to purchase CDS against CMBS will begin to tick up.

So the CDS for CMBS can potentially provide an in-depth look into the overall health of the commercial real estate market, which appears to be the next potential hot spot.

As the global economy sails into uncharted waters, we can look to CDS as the compass telling us where the next potential financial crisis might take place.

Yours truly,

TD

This newsletter is sponsored by Bybit. Be sure to try out the exchange here, and take advantage of all they have to offer today.