The Next Crisis Is Already Solved

The Blend: The Biggest Takeaways From Jackson Hole

MMT’ers have an uphill battle.

That’s my takeaway from my meander through the dozen or so articles, handouts, and even some essays in relevant publications that came out of the big event last week.

The event is the Jackson Hole Symposium, a meeting for central bankers to share their ideas on various topics. It happens each August in one of the least densely populated states in the United States, Wyoming.

For those who haven’t been to the middle states of the U.S., the state of Wyoming is harsh. It doesn’t get much rain. And whenever rain does fall, it's either whipped back into the atmosphere from the harsh winds, or it gets distributed to some farmer, city, or business downstream that might not even live in the state… or it’s falling in and around Jackson Hole.

It’s a race for survival.

And with the arrival of the group of individuals who arguably decide the fate of economies across the globe, it’s a highly metaphorical setup: the most well-off individuals occupying the main gem of a harsh state.

But I’d rather not get into a discussion of Oliver Anthony’s “Rich Men North of Virginia,” but instead dive into what these ivory-tower-walking elites have on their minds.

Knowing what and how they’re thinking can help us get into their minds. It can help us to better understand why they might make the policies they do. The idea here is to know how they will act, before they do.

Because that’s where opportunities sit.

Now, to get into a 2023 outlook type of essay requires me to scribble another ink bottle’s worth of verbiage, so I’ll hold back on that until my Single Origin piece next week. In that piece, I’ll dive into what looks to be the current trend of the financial system, what it means for the U.S. dollar, and even take a shot at trying to figure out where crypto fits into this future of finance.

For today, I’d like to do a special four-topic Blend on the Jackson Hole event. That’s because I found four main themes present in the papers as well as in various discussions taking place around the event.

It’s a good opportunity to reveal the broader strokes of what’s beginning to take form on a global scale. And it sets us up for a deeper discussion next week.

Alright, so let’s eat our veggies on some academia gobbledygook. And also showcase why MMT’ers days are numbered.

Also, if you stick around until the last section, I hit on an area of the market that central bankers are clearly worried might cause the next financial crisis, and what their solution to the yet-to-happen crisis will be.

OK, let’s get to it.

Central Banks Need to Change Their Thinking on Productivity

Number Go Up. NGU. It’s a “cure-all.”

We know this all too well in crypto. As asset prices rise, permissionless and decentralized blockchain technology becomes the greatest thing to ever happen in our society.

The media starts plastering various crypto founders and VCs on every magazine and talk show… And every move feels like the correct move.

The same theory applies to economic production, or GDP. When you have 100 million laborers working with more productivity, NGU. Every elected official’s policy that they implemented, every speech they gave, it all feels like it contributed to NGU.

Whether true or not, doesn’t matter. NGU cures all.

But once that number goes down… Well, things get ugly. And that number is starting to go down.

Which is why productivity was a major topic at the Symposium.

Professor Yueran Ma from the University of Chicago was one of the first guests to hit on this topic.

In her paper, she hit on this issue from the standpoint of innovation. More innovation leads to more productivity. It’s how NGU happens.

As far as why productivity is looking dismal, she points out how VC spending is related to interest rates. When rates rise more than 100 basis points (bps), VC spending drops. A period of fewer patents and lower productivity ensues.

It seems rather straightforward, but it’s more about the data gathered, techniques of analysis used, and making the argument irrefutable. Great work always seems simple – that’s what makes it great. But what really made this piece interesting were the recommendations given by the author.

She starts off stating that central bankers need to be open to new ways of looking at how monetary policy impacts innovation. To drive this point further, the author wisely looked back at past speeches from central bankers and noticed the word “innovation” is barely mentioned. Meaning to view innovation relative to monetary policy is fresh thinking.

By exposing this gap, she delivers three recommendations. Number one:

Should monetary policy be more accommodative on average, to the extent that innovation is undersupplied (due to high social externalities)? Recent analyses suggest that, depending on the properties of shocks, optimal policy may follow inflation targeting outside the zero lower bound, or may set inflation above target when subsidies for innovation fall short.

Aka, if innovation is low, cut rates to boost them. But that doesn’t mean dropping them to zero.

Second recommendation:

Countries with more countercyclical monetary policies experience higher growth, especially in industries that appear to be more financially constrained.

That’s a really interesting point. She’s suggesting we lower rates when we have global turndowns, and raise rates when things are looking rosy… While hard in practice, if successful, higher growth ensues for the country.

It’s a way to try to reduce the massively imbalanced rate cycles we’ve seen over the last few decades. These cycles last years. Each one moving from low to higher rates, then dropping them to zero in no time. Followed by a long period of low rates before starting over. This is not ideal for long-term growth.

Then the last and most important point:

Recent work suggests that fiscal policies could push the economy out of a stagnation trap…

This seems intuitive. Good spending from the government can result in more innovation. Aka, get your shit together, governments. You can’t just throw money around hoping something happens.

This poor spending is one topic that was pervasive throughout the talks. It was last year as well.

All in all, the topic of productivity is now being viewed through setting rates. It’s opening the door for a small rate cut when appropriate.

If we hear central bankers talking about boosting innovation through policy, this is your signal that a cut is coming. Finding clues like this are why we take the time to read through these studies, as bankers asked for them to be done in the first place.

There were several other presentations hitting on productivity. But this one stood out the most, as it brings monetary policy into the limelight. And offers us something to watch moving forward.

The next topic was on supply changes, which as you’ll see relates a bit to productivity…

Fragmentation: A Hidden Source of Inflation

This was another theme and really hits on a topic that’s more geopolitical than anything else.

Now, Foreign Affairs published a piece just a few days before the symposium. The author was Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Meaning this was more of a groupthink response from the IMF.

While the essay itself felt like a sales pitch for why the IMF needs more money to help save central bankers across the globe from a future financial crisis, there was another theme it honed in on.

It was the fact globalization is becoming a thing of the past. Since 2020, countries have begun to shift supply chains. Some of this was in response to political tensions. Other reasons centered on securing necessary resources for the country in tough times, like during the pandemic. Whatever the reason, it’s a global trend.

The U.S., for instance, is bringing chip manufacturing (among other industries) to its borders. It views it as a matter of national security.

While that’s fine, the side effect is global fragmentation is leading to higher prices. Items usually get produced where they are made most efficiently. But as soon as you bring other factors to the equation, costs rise.

Now, instead of an $80 chip, it’s $100 since labor costs have risen, the cost to acquire materials rose, the rent on the building is higher, human resource costs ballooned, and so on and so forth. These things add up – and they’re passed onto the consumer.

Fragmentation, or deglobalization, is hidden inflation. And as we continue to hear about BRICs meetings, Ukraine/Russia fighting, and other political jockeying… it comes at a cost.

Much of this was echoed by Laura Alfaro and Davin Chor in their paper submitted at the Symposium called “Global Supply Chains: The Looming ‘Great Reallocation.”

Main difference here is their study looked at the U.S. supply chain specifically. They noticed the country shifting away from China toward more involvement with Vietnam and Mexico. However, costs are being incurred along the way.

The added costs mean the economic output for any country following suit gets hit. That’s because if input costs are rising, it’s harder to turn each dollar into more dollars – aka, it affects productivity.

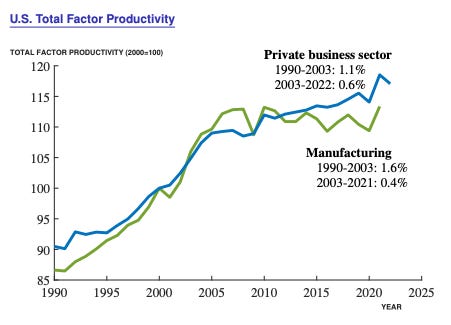

Meaning this chart (from a handout by Charles I. Jones at Stanford) is not improving soon.

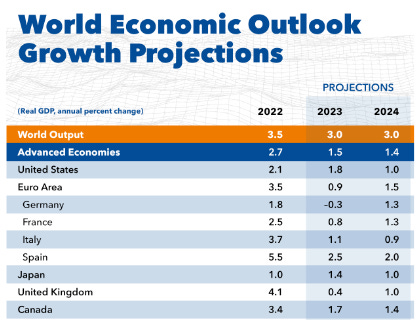

This stance and viewpoint looks to be a “take me serious” tone. We know this because the IMF dropped these figures just prior to the conference… It’s trying to sound the alarm.

The issues of productivity and fragmentation are huge. And they relate directly to this next topic…

Being Real About Debt

To sum up the symposium so far… Productivity is bad. Fragmentation leads to inflation. And in turn, makes economies less productive.

This means the economy might not be as profitable as it was before.

If this issue unfolds in a household that is up to their eyeballs in debt, we know the outcome… Falling credit scores, higher borrowing rates, and possible bankruptcy.

Now imagine the effects on an entire country.

When it comes to the U.S., no politician has taken this debt issue seriously. In fact, MMT’ers are gaining in popularity again as presidential talking points start up around unsustainable government debt levels.

The belief with MMT’ers is they can control inflation. And instead of issuing Treasuries, they can just go directly to the Fed and print money.

Anybody in crypto knows this is insanity. What happens if users of a proof-of-stake chain suddenly unstake all their tokens from the network? Massive unlocks result in lower prices. For the United States or other countries, this turns trillions of dollars into liquid dollars – hyperbolic inflation.

If it didn’t impact my purchasing power, I’d love to let that scenario play out and watch that inflation hysteria unfold for MMT’ers.

The truth here is that MMT looks to be a direct byproduct of hubris. The belief that the trust of the U.S. dollar is as sure as gravity on Earth is myopic. A quick glance through history ends these conversations and is in part why the Federal Reserve is intended to be independent.

But logic only goes so far. Luckily, Barry Eichengreen from the University of California, Berkeley dropped a paper that knocks MMT’ers down like a rubber mallet to a groundhog.

I’ll start off by quoting the paper to give you a taste of the argument:

...persistent primary budget surpluses are not in the political cards. Over the last half century, episodes where countries have run primary surpluses of, say, 3 to 5 percent of GDP for extended periods are very much the exception to the rule. Maintaining large primary surpluses requires favorable economic conditions and a degree of political solidarity that currently do not exist. Divided government and slow growth make this route to debt consolidation even more challenging than in the past.

High public debts are not going away anytime soon. But they must be dealt with. That’s his main takeaway.

The author doesn’t suggest how to overcome this fact of life, but instead seems to strike a cautionary tone. One that says, “Do not ignore these debts. While they are here to stay, if you make any of the wrong decisions as laid out in this paper, you’re in for trouble.”

The difficulty of overcoming these debts is addressed as well. Per the papers earlier… Lower productivity, fracturing global supply chain, and loose spending by governments… Debt is here to stay. Just don’t be hubristic about it.

Again, not a handbook on what to do… Just a discussion on what not to do. Inflating debts was a no-go… MMTing money was a no-go… certain capital controls were another no-go. Meaning these things should not be considered today.

And with that paper sort of tying a bow on the conference, the symposium seemed to be well-choreographed.

These papers were rolled out in a strategic sequence. Presenters offered proof of certain issues. Laid out the fact that tough times are truly ahead. And simply said these debts are here to stay for the reasons mentioned before. Your situation is dire.

Good luck.

I was left feeling a bit hopeless, to be quite honest. But this next topic is where I started to get a bit excited again…

The Solution to the Next Crisis

Outside of crypto, Treasuries is the topic I talk about most.

That’s mostly because the bond market tends to be where things heat up before the effects trickle into the rest of the economy and the markets.

So having a finger on this market’s pulse is essential for success.

Now, at the symposium, there was a paper discussing issues with the U.S. Treasury market. For a bit of background on why this is important, the topics and papers discussed at the symposium are essentially topics that were requested by the attendees.

Meaning the Treasury market is on the forefront of central bankers’ minds.

And for good reason, as shown by this paper from Darrell Duffie out of Stanford. In it, Duffie explains an issue beginning to show itself in the market.

Particularly, dealers are running out of room to absorb Treasuries. Treasuries are an asset. They are not a dollar nor equity. This means there is a certain amount of risk attached to the bond.

Per regulations, these dealers need a certain amount of cash on the books relative to the amount of Treasuries they are issuing… Because they come with a degree of risk. We don’t want dealers becoming insolvent.

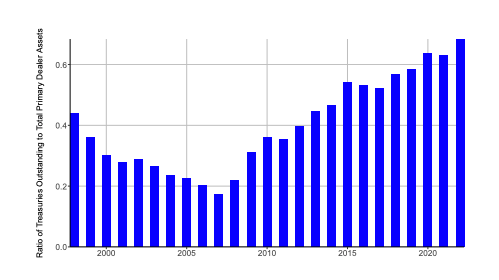

For those that have been following along, the amount of Treasuries being issued into the market is rising. As a result, dealers are running out of room. They are dealing with a capital constraint. Meaning this balance sheet issue is growing in significance.

You can see this in Duffie’s chart below, which shows the ratio of Treasuries to dealer assets.

Here’s why this matters according to Duffie:

When dealer balance sheets are sufficiently loaded, the propensity of dealers to supply liquidity is reduced and the demand for liquidity that dealers request from other dealers rises.

That’s a liquidity problem.

There’s a lot more discussion around this, but instead of going into the weeds, let’s skip to the fun part: The proposed solution.

Right now, this market is fairly centralized. There’s a central book that dealers can tap. And anybody buying bonds works with the dealer. There is no customer-to-customer market.

The author believes this is an issue. And by increasing market participation through a more decentralized orderbook – no, not blockchain – we will have deeper liquidity… And more resilience as a result.

It doesn’t stop there, either…

There are even discussions on loosening up regulation that would free up dry powder on dealer books. When reading this, I thought to myself, “This right here is the solution in black and white to what many in the market believe is the upcoming crisis: the liquidity crunch due to quantitative tightening and more Treasuries being issued.”

My guess here is that these policies and emergency powers are already written for the day they’re needed. The Fed just needs to use its congressional powers that let it act for price stability.

If that day comes, it’ll be a strong buy-the-dip indicator. But most importantly, it will set into motion what seems to be the future of the global financial system.

A topic I’ll hit on next week.

Until then…

Your Pulse on Crypto,

Ben Lilly