The Economy’s Healthy Appearance Is Only Skin-Deep

Macro Update: Three Blind Spots Primed to Blow Up

If the U.S. economy were a person, do you think it’d pass a complete physical checkup right now?

The average investor might say yes. After all, the U.S. equity market has been in melt-up mode in 2023, with the Nasdaq and S&P 500 looking to break all-time highs.

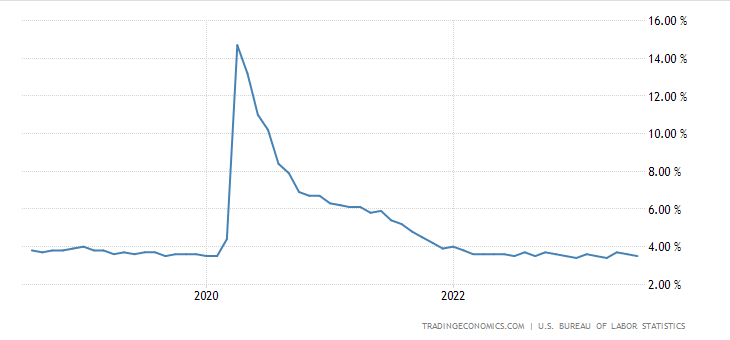

Another bright spot is the job market. The latest labor report shows the unemployment rate decreased to 3.5% in July 2023. Since the start of 2022, unemployment has managed to stay under 4%, matching pre-pandemic levels.

Surprisingly, wage growth also remains steady and increased 5.97% year-over-year (YoY) in June. That’s comfortably above the latest YoY inflation rate of 3.2%.

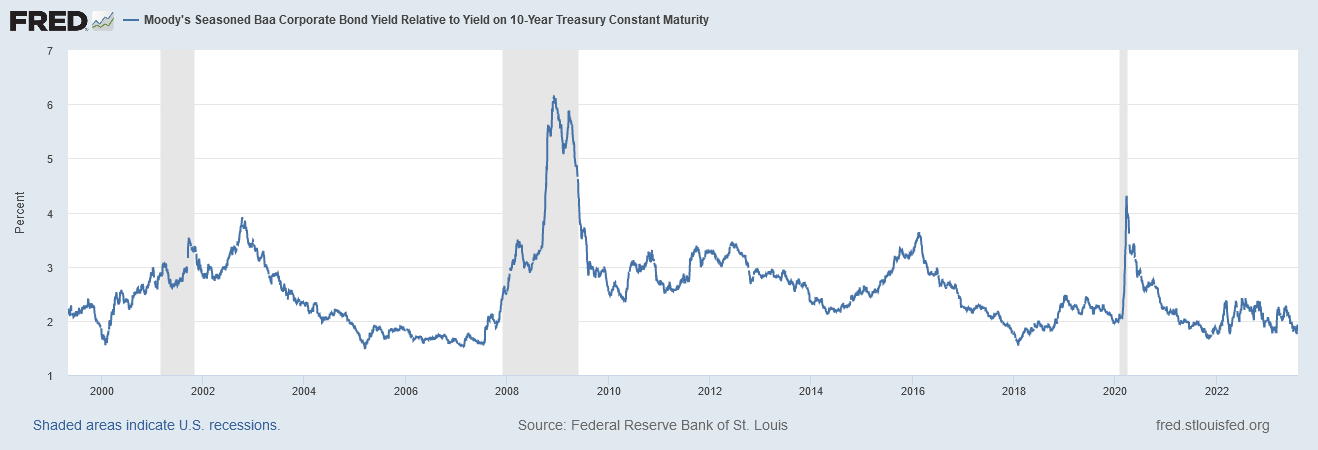

Also, the credit spread between corporate bonds and Treasury yields has been surprisingly holding steady.

If you remember from my essay in April, a credit spread is how much more interest a corporate bond pays compared to a U.S. Treasury of the same duration. When the spread is small, it’s easier and cheaper for companies to borrow money, which means the economy is healthy.

The spread between the Baa/BBB tranche of corporate bonds and the 10-year Treasury is around 1.89%, which is in the lower range of the past 23 years.

So far, the checkup seems to be going well. The economy might be getting out of here with a clean bill of health.

But when we probe deeper…we find a whole host of issues: high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, organ failure, and even tumors.

In other words, the good news is, the economy’s skin complexion looks great…and that’s about it.

Below, I’ll unpack three overlooked sectors that are starting to rot on the inside, making it a matter of time before the Federal Reserve has to step in for some major, life-saving surgery.

Let’s start off by continuing with the topic of corporate credit, which isn’t as healthy as it seems.

The Honeymoon for Corporate Credit Is Over

Like I mentioned above, the spread between the Baa/BBB tranche of corporate bonds and the 10-year Treasury is pretty low at the moment, as you can see in the chart below.

The sharp upward spikes that we saw from the 2000 dot-com bubble, the 2008-09 subprime mortgage crisis, and the 2020 Covid pandemic are nowhere to be found.

This is interesting, because despite the most aggressive hiking scheme in the Fed’s history, the credit market for the private sector is still stable and the expected volatility never materialized – at least for now.

Part of the explanation is that the cheap debt that corporations issued for years under a regime of low interest rates has yet to mature.

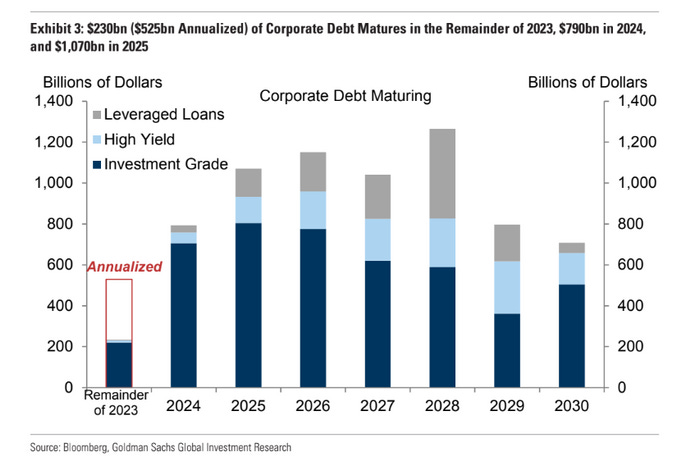

But that is about to change. The “wall of maturity,” the period in which much of this debt will come due and have to be refinanced at today’s higher rates, is coming soon.

According to Goldman Sachs, the wall of maturity for over $1.8 trillion worth of corporate debt will hit in 2024 ($790 billion) and 2025 ($1.07 trillion). This is after another $230 billion matures by the end of 2023.

As the chart above indicates, 2023 has over $500 billion of corporate bonds matured or maturing while 2025, 2026, 2027, and 2028 all have over $1 trillion worth. In fact, 2023 has the lowest amount of corporate bonds maturing all the way up to 2030.

And when that debt has to be rolled over, corporations can expect to pay much higher interest.

Below is a chart of the yield for AAA (red line) and BBB (blue line) corporate bonds since late 2019. The AAA tranche was at 2.03% at its lowest. Today, it’s at 4.85%. The BBB tranche was at 3.14% at the trough. Today, it’s at 5.92%.

The honeymoon of cheap corporate financing is over. Should these companies need to roll over their debt today, they can expect a two-percentage-point increase in their debt financing cost. Goldman also estimated that for every dollar that financing costs go up, there’s a 10-cent drop in capital expenditures and 20-cent drop in labor budgets – i.e., less hiring and more firing.

Therefore, we can expect additional unemployment, shrinking corporate operation and activities, and slower business growth on the way.

Goldman predicts a loss of 5,000 jobs on monthly payrolls in 2024 and 10,000 in 2025. Not to mention that corporate defaults in the first six months of 2023 (55) have surpassed the entire year of 2022 (36) by 53%.

The Next Domino to Fall?

Commercial real estate (CRE) is certainly on everyone’s mind lately. We’re seeing more and more headlines showing that Pimco and other office building management companies are defaulting on payments while office buildings are being sold well below value. Plus, local and regional banks are under stress because they’ve issued plenty of commercial real estate loans this year.

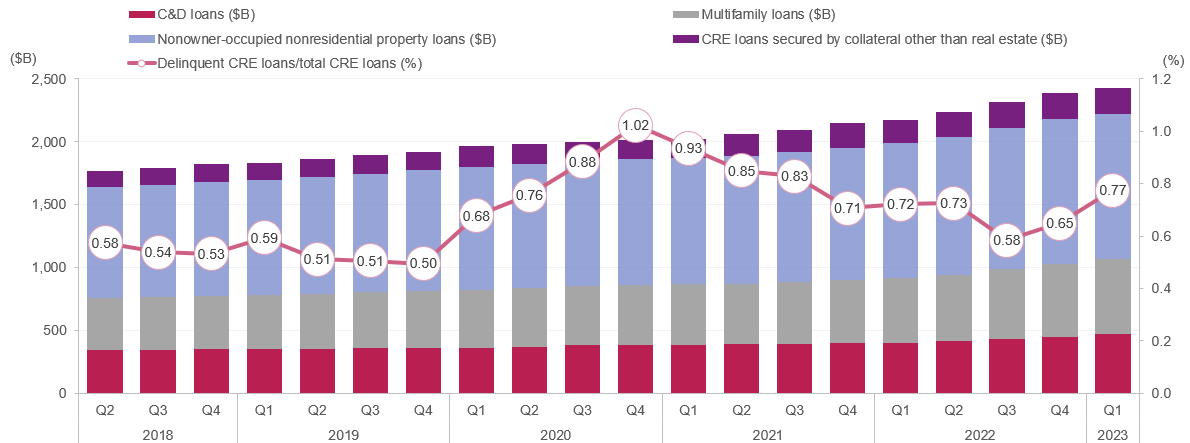

Similar to corporate bonds, CRE debts have a $1.5 trillion wall of maturity due by the end of 2025.

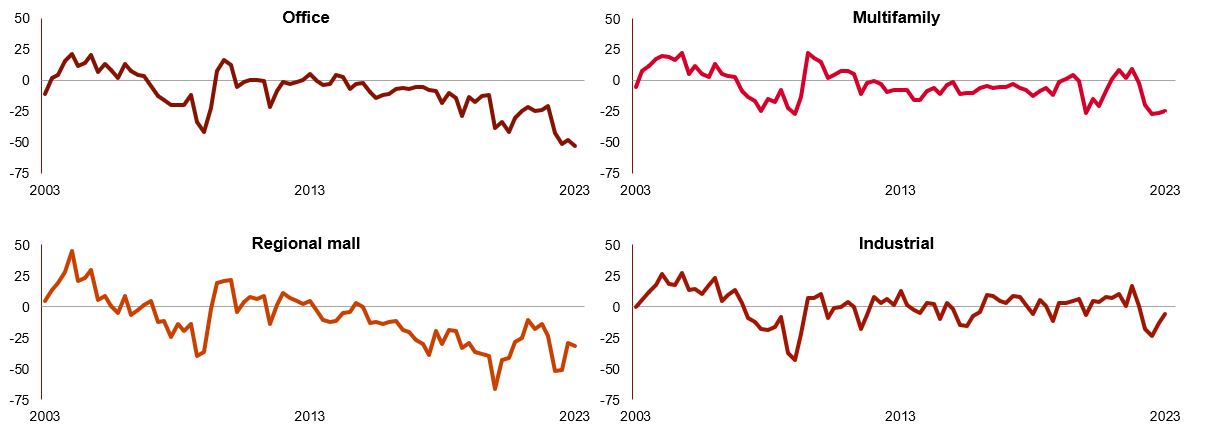

Below is a chart of median discounts of net asset value (NAV) for different types of real estate, ending at Q1 of 2023. Whenever there is a discount to the NAV, it means there’s a bearish outlook on the asset and its ability to perform or generate cash flow.

As we can see, while all the CRE sectors are trading below the median NAV, the multifamily and industrial sectors are starting to trend up. On the other hand, the office and regional malls are trending way down with no signs of picking back up.

The delinquency rate for CRE loan repayments is ticking back up as well. The chart below shows the amount of different types of CRE loans going back to 2018. But the numbers we want to focus on are in the white circles, which show delinquency rates rose to 0.77% in Q1 2023 – the highest in almost two years.

Rising vacancies, lack of demand due to more remote workers, companies slashing operation costs, higher interest rates, higher financing costs, and a surplus of office buildings are making commercial real estate a very unattractive investment (except for multifamily housing).

We’re starting to hear news that building owners are selling their properties because the loan on the building is more than the value of the building itself.

These issues can have a deeper impact on the economy than just triggering another local or regional bank crisis. The less-discussed impact is how they negatively affect pension funds and insurance companies.

Because of the low interest rates of the past few years, pension funds and insurance companies couldn’t find enough high-quality liquid assets to invest in and match their long-term liabilities.

Investing in Treasuries that pay a meager 2% while you have to pay 7% to pensioners just does not work. So pension funds and insurance companies turned to other investment vehicles, such as commercial real estate trusts, to garner a higher yield and fulfill their financial obligations.

Should the commercial real estate market continue to falter, it could spell trouble for these entities.

Credit Card Debt Is Having a Record Year

We can’t forget the impact of the general public.

People have been piling on credit card debt at an astounding rate.

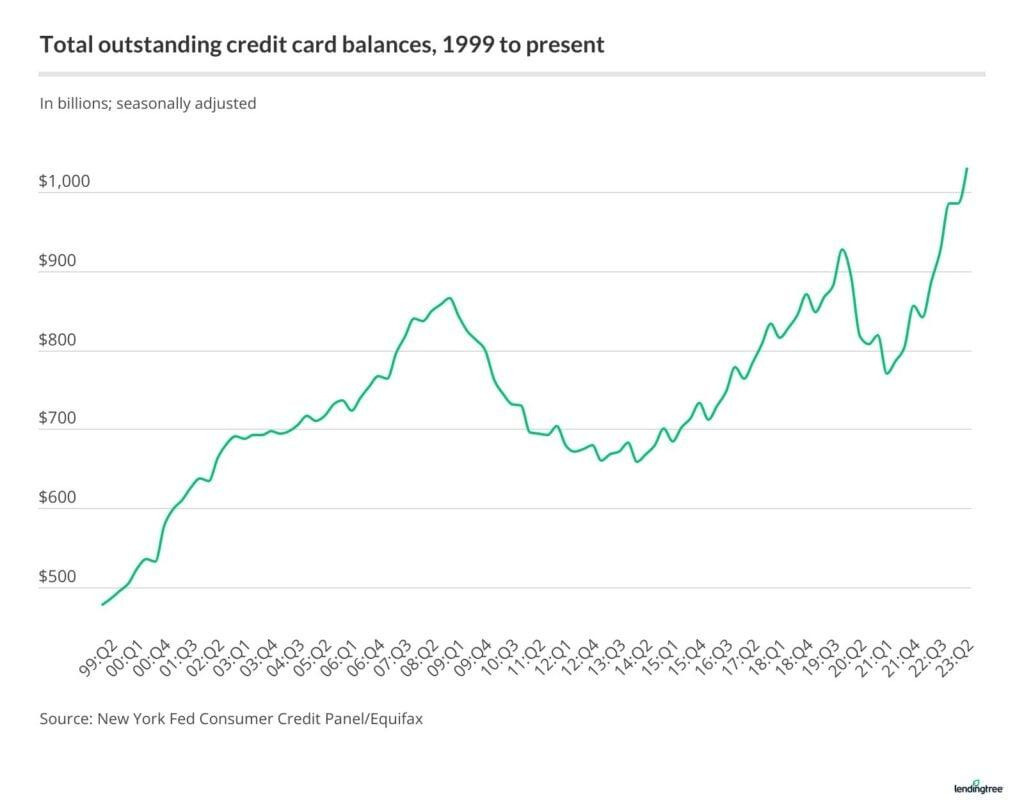

2023 so far has been a record-breaking year. In Q2 of 2023, for the first time in U.S. history, credit card balances climbed above $1 trillion.

But unlike 2007-2009 or 2017-2019, when credit card balances were high as well, credit card interest rates today are much higher, between 20-22% annualized. In the chart below, the turquoise line is the average interest rate of credit cards going back to 1994. 2007 to 2009 credit interest was at a range of 12-14% while 2017 to 2017 was at 13-15%.

As it stands now, 47% of credit card holders are carrying a month-to-month credit card balance. This is slightly above the 46% from Q4 of 2022. Data from Bankrate also shows that 60% of that 47% that are carrying balances have been rolling over their balances for longer than a year.

Hence, it is not surprising that the 90-day delinquency rate for credit cards is picking up, rising from 3.35% to 5.05% between the second quarters of 2022 and 2023.

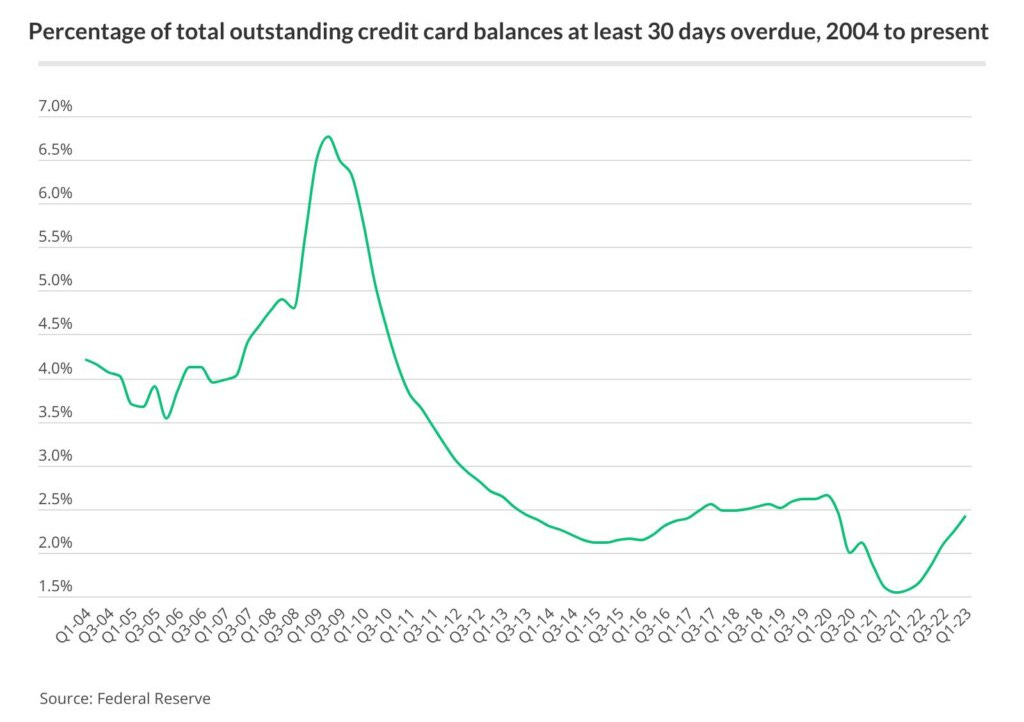

The delinquency rate for 30 days is a bit easier on the eyes, just under 2.5%. But it looks like it is heading back up.

As the economic conditions become more stringent, we can expect the use of these credit facilities as well as services such as buy-now pay-later (BNPL) establishments and paycheck advancement to increase.

Burn, Baby, Burn

The normal economic cycle of expansions and recessions is a key component to a healthy economy. The same goes for a balanced government budget and adequate level of debt and leverage.

But decades of money printing, lower interest rates, and government overspending have corrupted that cycle and led us into the crisis we’re facing today.

Think of it this way: California has been plagued by wildfires in the past couple of decades. But California has always been prone to wildfires, and in fact, the state’s ecosystem is designed to benefit from them.

The state’s giant sequoias and coastal redwoods cannot reproduce without wildfires. Their cones will only pop open and spread the seeds inside when fire burns it. And then the warm gusts from the fire will carry the seeds away to germinate somewhere else.

The fire will also burn away the dry kindling, underlying vegetation, and dead trees and turn them into fertilizer.

Because of this, wildfires were more subdued and less intense because they happened frequently, which in turn reduced the number of dead trees and dry kindling that served as fuel for the fire.

Fast forward to now: Mankind has suppressed naturally occurring wildfires. Also, the local and state governments do not have the money nor the manpower to manage the forest adequately (including clearing and removing of dry kindling, dead tree, and underlying vegetation), so the fuel for the fire just kept accumulating for years if not for decades.

All it takes is one spark and some winds to start a ravaging wildfire disaster in California.

Now, imagine the financial markets are the people trying to suppress the wildfire; the Fed and the government are the forestry service that cannot clear out the fuel for the inferno (by trying to prevent recessions and intervene in the normal economic cycle); and all the debt, leverage, and liquidity are the dead trees, dry kindling, and underlying vegetation that will provide the energy when the fire starts.

The bottom line is: No one knows what is going on. It is truly uncharted territory. Everything that is happening now in the economy has never been seen before. That is why all the traditional indicators are off their marks.

How the central bankers will navigate these waters is anyone’s guess. And the most disturbing notion is that they don’t know either. So don’t put too much faith in them.

The government doesn’t have the tools to fix things either. And even if it did, it lacks the willpower and determination to fix what will be coming.

The free market died a long time ago. The market dynamic is different now.

We are truly witnessing history in the making.

It won’t end well.

Yours truly,

TD