Despite the Fed Pause, the Market’s Barometer Is Signaling Danger

Macro Update: Why the 10-Year Treasury Yield Won’t Stop Rising

With a heavy heart, let’s first start off by sending positive vibes and hoping that the kinetic wars that we are currently witnessing can end soon.

Regardless of political opinions and other reasons, innocent civilians, young and old, are suffering and dying.

Here’s to wishing that these conflicts can end soon without escalating to a full-blown world war as well as put an end as soon as possible to all the pointless suffering and needless dying.

October is generally considered one of the market’s most volatile months. And thanks to recent events, it’s living up to its reputation this year.

To start, there’s plenty of mayhem in and around the U.S. government. The country barely avoided a shutdown at the start of the month. Kevin McCarthy, the Speaker of the House, was removed, and Congress has yet to agree on a successor. And the U.S. government debt just passed $33 trillion.

Add in the geopolitical chaos occurring in the Middle East, along with the ongoing war in Ukraine.

All this doesn’t do much to quell the market’s nerves.

Luckily, the financial market is catching a long awaited breather from the Federal Reserve. After raising rates constantly throughout this year and last, the Fed declined to raise the Federal Funds Rate (FFR) at its September meeting.

One would speculate that amid all the global turmoil, the pause from the Fed would provide some relief on the cost of capital for the economy…

But that is not the case.

The market has another force to contend with: The rising 10-year Treasury yield.

It’s a good barometer of the health of the financial market, as it usually reflects how investors view current conditions. So what exactly is it?

Let’s quickly break down Treasury yields, how they affect the market, and why the 10-year yield has veered off its normal course this time around.

Why Treasuries Are Like Season Tickets

In its simplest form, a Treasury yield just means how much annual return an investor can expect from owning a government bond. When you buy a Treasury, you’re loaning money to the U.S. government, which promises to pay you a certain amount of interest to compensate for your risk.

Each Treasury comes with a coupon rate, which represents the fixed amount of interest the Treasury holders will receive. However, this isn’t the same thing as the yield, which can fluctuate depending on the value of the Treasury in the secondary market along with its remaining tenure (time to maturity). For that reason, the yield is usually expressed as an annualized percentage.

Here is a snapshot of the U.S. 10-Year Treasury Note.

The yield is currently at 4.980%, but the coupon is only paying 3.875%.

So this bond only pays 3.875% of interest, but investors and the market are demanding a higher payout.

Because of these factors, yields usually move inversely to Treasury prices. If the yield goes up, the bond (or in this case, the Treasury) price goes down, and vice versa.

It is precisely this dynamic that makes Treasury yields, especially the 10-year, a good barometer of the health and sentiment of the financial market.

The easiest way to think of it is comparing it to owning season tickets of a sports team…with one extra wrinkle.

A common practice for season ticket owners is to sell the tickets for games they cannot attend via online secondary ticketing platforms. But they don’t usually sell all the tickets at once, and because ticket prices fluctuate over the course of a season, it’s possible to sell some tickets for a profit or loss.

To make this comparison easier to understand, let’s say that I am a season ticket holder of the NFL’s Kansas City Chiefs (KC).

The season has 10 games, and I need to sell the tickets for all 10 games because I cannot use them.

KC is a title contender. So I had to pay $100 per ticket.

But depending on the opponent of each game, the health of KC’s players, and whether the team is doing well or poorly, the buyers might be willing to pay over $100 for one game and only $75 for the next one.

As an example, if both KC and the Las Vegas Raiders are in contention for a playoff spot and everyone is healthy, I can sell that game for $150. But if Patrick Mahomes is injured and cannot start (or Travis Kelce is depressed because he broke up with Taylor Swift), then I might only be able to sell the ticket for $50.

Not to mention the closer we are to the game date without a taker, I will have to lower the ticket price to entice buyers.

So, each game is different, and there are factors that dictate whether I will be able to get my $1,000 at the end of the season. The same logic applies to long-term Treasuries.

If the market thinks that the U.S. government is going to default and become unable to pay its debts, then Treasury prices will fall due to excess supply and weak demand. Instead of paying the $1,000 face value of the Treasury, buyers are only willing to pay $980.

But how does this affect the yield?

The Canary in the Coal Mine

Going back to the season tickets…let’s say for each game, you also could make a bet on whether KC would win or lose that game. And the size of that payout would change based on the odds, or whether KC was expected to win or lose that game.

For example, if KC is on a three-game winning streak, and they’re playing the Raiders who are last place in the division, they’re probably expected to win that game. And ticket prices are high, because the team is hot right now.

But the payout of your bet is low – because KC has good odds of winning.

The bet payout is similar to a Treasury yield. And just as ticket prices and payouts have an inverse relationship, so do Treasury prices and yields.

If Treasury prices start to go down because of fears of a U.S. default, Treasury yields will go up, in order to attract investors to buy newly minted Treasuries.

On the other hand, if wars are breaking out and investors are looking for a flight to safety, investors will probably turn to U.S. Treasuries, long considered one of the risk-off assets to own as a safe haven. The strong demand and low supply drive Treasury prices up and yields down.

Similar to the season tickets and the sports bets, the value of both all depends on external factors and unforeseen events.

This is why Treasury yields are usually a good canary in the coal mine that can hint at what might be coming for the economy.

And the yield to focus on is usually the 10-year U.S. Treasury.

The Guiding Hand of the Economy

While there are 20-year and 30-year Treasuries, the 10-year Treasury yield is the benchmark that everyone uses to gauge the vitality of the economy.

It is also a major factor when it comes to the lending rate. The 10-year yield has a tremendous impact on borrowing costs in almost every aspect of our lives.

For instance, while the Federal Funds Rate (FFR) determines the adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM), it is the 10-year Treasury yield that serves as the benchmark for the 15- and 30-year fixed mortgage rates. In this case, they all move in the same direction, e.g., when the 10-year yield goes up, the others go up as well, and vice versa.

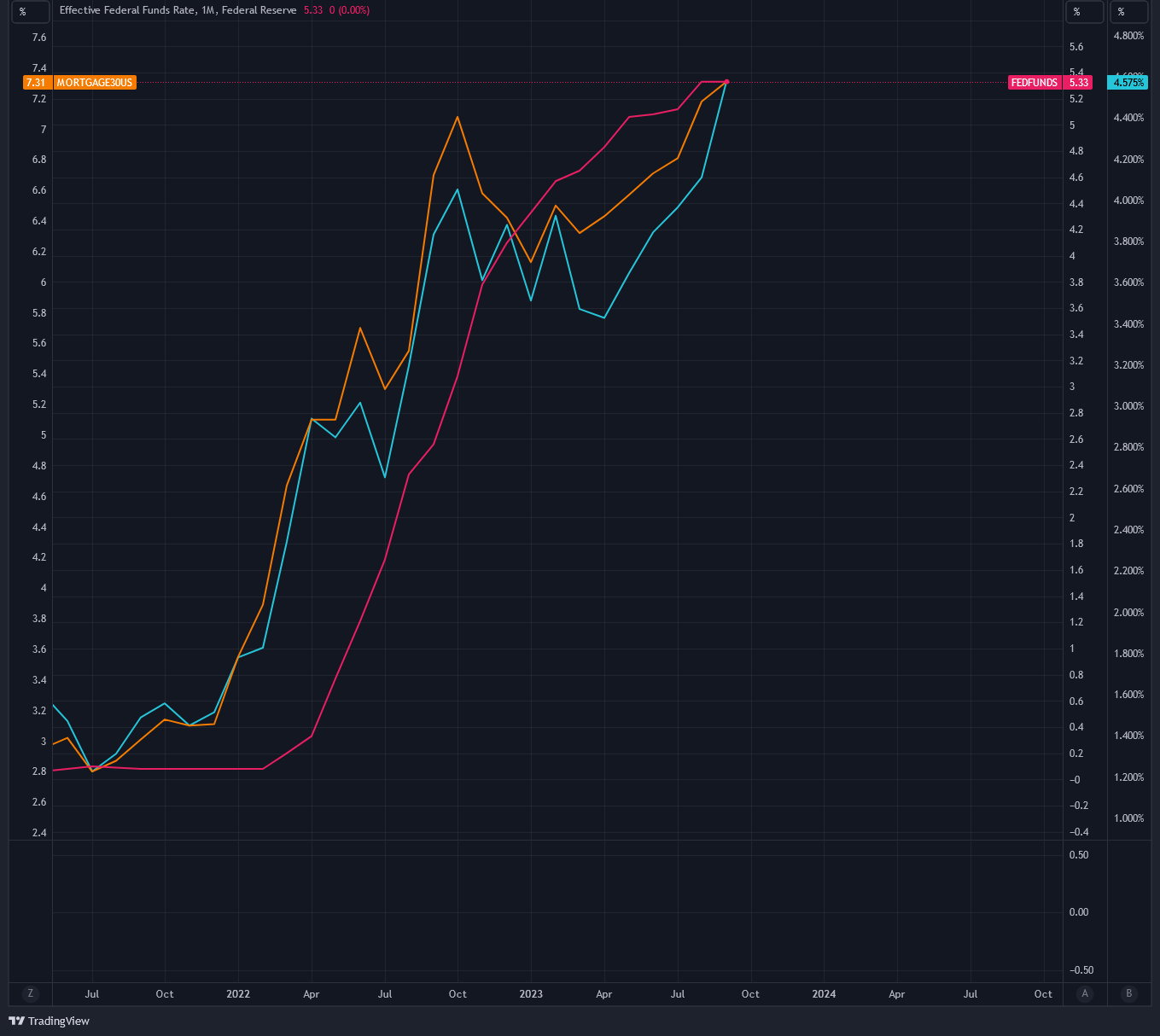

Please look at the chart below. The turquoise line is the 10-year Treasury yield, and the orange line is the 30-year fixed mortgage rate. Both lines follow each other closely, while the FFR (red line) is not so precisely correlated.

The 10-year Treasury yield also has an impact on the corporate lending rate. This rate dictates the cost of capital for private companies. If the 10-year yield is high, it can choke off economic growth via reduced company expansion.

The stock market is another component of the financial market on which 10-year Treasury yield has tremendous influence.

When the yield rises, that usually means the market is not healthy and the outlook is gloomy, because investors are looking for higher returns outside the stock market. On the other hand, a falling yield can be interpreted as investors are looking to take on more risk, and all risk-on assets should do well, including the stock market.

As one can see, the 10-year Treasury yield has a tremendous amount of influence in our lives.

Through the Looking Glass

One would think that with the current state of the geopolitical landscape, investors would be flocking to Treasuries, especially the 10-year, and triggering yields to fall.

But that is not the case anymore.

We are seeing the opposite. Yields are actually rising. The chart below shows that the 10-, 20-, and 30-year Treasury yields (yellow, orange, and blue lines, respectively) are all going up.

In fact, late last Thursday, we saw the 10-year yield actually rise above 5% – a level it hasn’t hit since July 2007.

What we are witnessing is investors are selling Treasuries instead of buying them.

There are several potential explanations.

One is that investors have lost confidence in the U.S.’s ability to pay back its debt due to its unscrupulous spending and massive deficit.

After recently surpassing $33 trillion, the U.S. debt is not going down anytime soon. And we can expect it to continue to rise because of war funding for Ukraine and now Israel, with President Joe Biden expected to ask for $60 billion in aid for the former and $10 billion for the latter.

And with higher rates, the government is paying more interest on that debt. The chart below shows its skyrocketing interest payments. As of October 2023, it’s at $90.58 billion. This number will only get bigger, not smaller.

The market feels that the U.S. government will have a difficult time to service its debt obligations in the future; hence, it’s selling off U.S. Treasuries.

Second, countries in the BRICS group (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) are ramping up their efforts to escape the U.S. dollar system. For example, Russia and China have been offloading U.S. Treasuries, which has created excess supply in the open market.

China has sold off $40 billion worth of U.S. Treasuries since April, with a total of more than $300 billion since 2021.

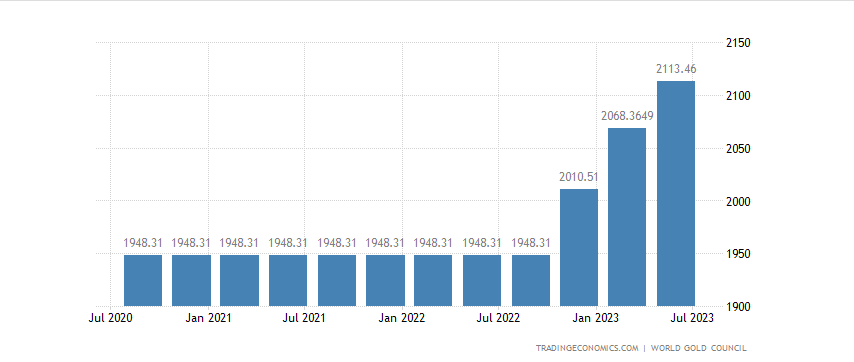

Where did all that money go? Below is a chart of China’s gold reserves since mid-2020.

China has been buying up gold.

With the rising gold prices of late, gold is in demand, and it might possibly be regarded as a safer place than Treasuries to put money into.

Finally, Treasury yields usually rise when the market is expecting inflation in the near future. Given the sticky nature of our current inflation, and the fact that it is stemming from supply-side problems and not demand, the market is indicating that it does not believe that inflation is going to go away anytime soon.

Doing Powell’s Work for Him

When Treasury yields, especially the 10-year, are high for a prolonged period of time, it is telling us to expect volatility and turbulence ahead.

What’s so serious about this period is that it’s clear the market is losing faith in the U.S. government’s ability to rein in spending and run a balanced budget. It also means that the market does not believe that the U.S. can repay its debts should its excessive spending continue.

All this is bad news for the “waiting for the Fed to pivot” crowd.

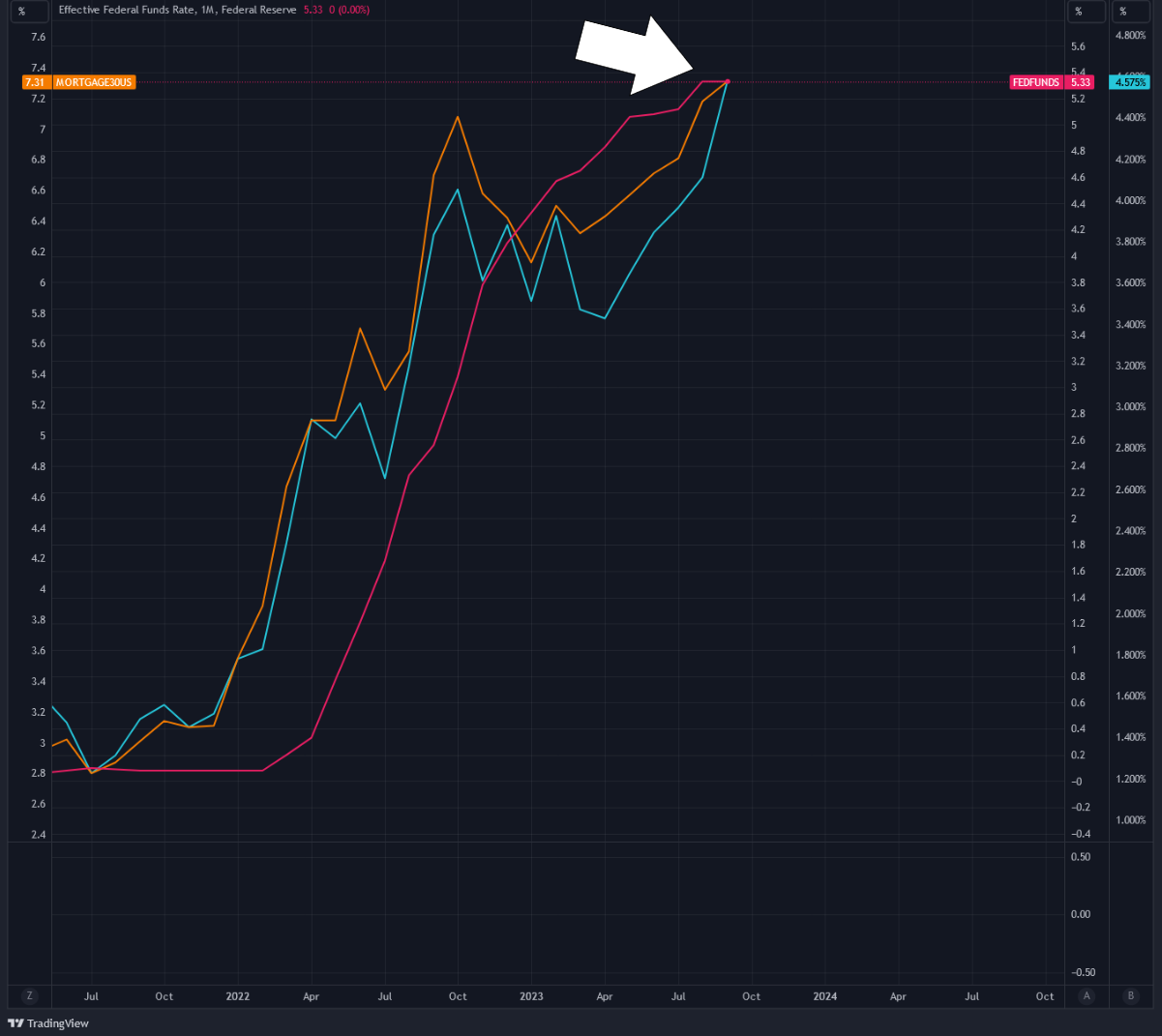

Corporate lending rates, mortgage rates, and borrowing rates can continue to rise despite the fact that the Fed has stopped hiking.

The chart below shows that even after the FFR (red line) stopped hiking in July, the mortgage rate (orange line) is still climbing and mimicking the movement of the 10-year Treasury yield (turquoise line).

When Fed chairman Jerome Powell stated rates would remain “higher for longer,” he was not wrong. After all, if the 10-year Treasury yield continues to rise, borrowing rates will rise as well, no matter if the Fed pauses rate hikes. The market will do the Fed’s job for it, without Jerome having to lift a finger.

Yours truly,

TD